Wristwatch Stoicism: A Visual for Key Stoic Ideas

By Stephen Dewitt

Welcome to Stoicism Today, the online journal for Modern Stoicism. This week’s essay is from Stephen Dewitt, a professor of cognitive psychology at University College London. We hope you enjoy his visualization technique for keeping Stoic principles top of mind.

Upon all occasions we ought to have these maxims ready to hand…

Epictetus, Enchiridion

I am an associate professor in cognitive psychology at University College London and have been practising Stoicism for nearly 10 years thanks to its revival by the members of Modern Stoicism and others. I have a busy home life with two- and four-year-old daughters that provides almost constant opportunities to practise living better. I have a background which also includes behaviour change and habit theory and I am very interested in the Stoic concept of good ‘self-talk’ and the ways in which we can maximise our chance of having useful Stoic concepts to hand when a given difficulty arises.

In my developing practise I found there was a long period of time where I had a good understanding of Stoic theory but still found it difficult to put into practise. After a period of anger or handling something poorly I would remember some core Stoic principle which, if I had brought it to mind at the right time, would likely have helped. So, rather than being primarily theoretical, this is a highly practical article about a mental trick for keeping more of the right thoughts to hand when you need them.

I’ve tried lots of different schemes myself and in this article, I want to lay out one I have been using now for many years. It has several useful properties. It is visual: humans are known to have remarkable visual memories and well known ‘memory palace’ techniques show how much we can remember when we attach concepts to a visual structure. It also involves a real physical ‘talisman’ (spoiler alert: your wristwatch), which acts as a physical, ever-present reminder to engage with the associated ideas. This is a common idea in contemplative practises, such as a Buddhist monk’s mala beads.

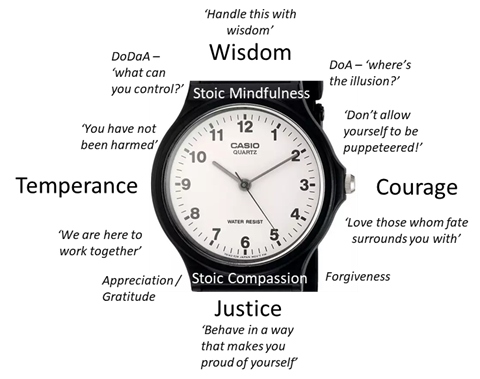

The basic idea is that we use the 12 points on the watch face to represent key Stoic ideas, arranged in a logical structure tailored to you. The first reason this works very nicely, and I hope will entice you as much as it did me the first time I realised, is that the four major points (12, 3, 6 and 9) align with the way the four cardinal virtues (going clockwise: wisdom, courage, justice and temperance) are often arranged. This provides the basic conceptual structure, and we can use the remaining 8 points on the clock face to mentally ‘pin’ other ideas that are related to those major virtues. For example, we might ‘pin’ more social ideas down by justice and more ‘wisdom’-like ideas up by wisdom (ok I know it’s all wisdom, but this is not primarily about tight definitions and Stoic theory but about producing good personal outcomes and working with your individual mental associations). Arranging things semantically like this makes it easier to remember and makes the whole structure feel more like a Stoic ‘space’ around which you can mentally explore.

When I say we ‘pin’ things to our watch face, this is all primarily of course in your mind. However, I do recommend you create a real representation of your personal version, on paper or digitally, like you will find further down this article. This will especially help at first, but it won’t be long before you will find it very easy to remember everything in your head if you get into the habit of using it regularly. Physically writing it out in a journal or scrap bit of paper is always a nice way to rehearse though.

Before we get into the details, another thing I like about this is that the traditional analogue wristwatch itself is one of the few modern relics we still regularly carry that we associate with an older time. Not as old as Greek / Roman stoicism of course, but of traditional values perhaps. It also of course has a somewhat obvious association with time which is important to Stoic practise in many ways (e.g., transience, the long view), so, while this might feel a bit hokey, to me it’s nice to at least feel like the association of Stoicism with this object is not entirely arbitrary. Of course, if you have a digital or smart watch this can still work, these modern versions can still act as the physical reminder of that older form. Even if you choose not to wear a watch at all, the mental visualisation is still a powerful tool as we all have such a strong mental model of the 12-point watch / clock face.1 We will talk further down about ways to maximise the ‘reminding’ force of your actual physical watch, so you don’t become numb to it.

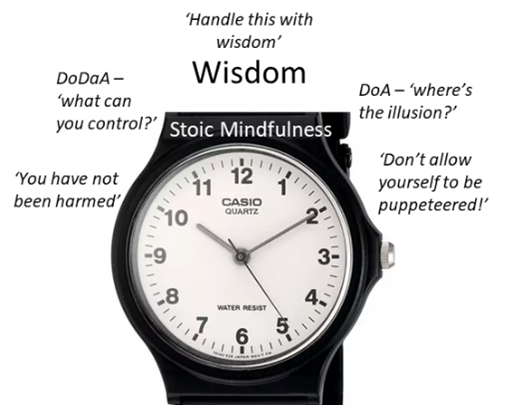

What you actually mentally ‘pin’ to your watch face is going to be highly personal, but there are some key Stoic ideas that would make sense for a lot of people. In the following I will lay out the ones I use. I have the ‘discipline of desire and aversion’ at ‘11’, and the ‘discipline of assent’ at ‘1’, either side of wisdom at ‘12’. In many cases, when engaging with this structure as a reactive practise, in response to some difficulty, I have a question that I ask myself associated with these points. For the Discipline of Desire and Aversion point I ask myself ‘What can you control?’. For the Discipline of Action point I ask myself ‘Where’s the illusion?’ (if you are angry, even if the person really has done something wrong, there will be some level of illusion, even if just of the magnitude of their crime, the level of intention behind it, or your certainty). For wisdom I ask myself ‘What’s the wise way to handle this?’. Questions tend to prompt creative thinking, but commands such as ‘Handle this with wisdom’ can also be powerful. You may like to paraphrase famous sayings or it might be more powerful for you to have exact quotes, feeling as if the person, e.g., Marcus Aurelius or Epictetus, is guiding you through the difficult situation. They need to be simple and short though; you should be able to bring them to mind even in the middle of a difficult situation.

Below these, at ‘10’ and ‘2’ I have bits of self-talk that are related to those two disciplines but which I find of great further value. At ‘10’ I have ‘You have not been harmed,’ which I find a useful thing to remind myself of in many situations, for example perceived insults to my ego. At ‘2’ I have ‘Don’t allow yourself to be puppeteered.’ This is a paraphrasing of an excellent argument by Epictetus which I only came across within the last few years. The argument first asks if you would allow a person to take your arms and legs and do with you what they will. Most people would not allow this. So then, Epictetus asks, why do you allow this person to, with a single sentence or even a word perhaps, reach into your mind and puppeteer your emotions? Many of us give this power to people like family members with whom we have difficult relationships. We might go into a meet up with them saying to ourselves ‘They had better not say that or I’ll explode.’ Epictetus reframes this very common tendency to show that you are simply handing over a button to someone that they can press and just ‘switch on’ your anger. Utter madness! I find this argument so powerful as I think it taps into my identity as a highly independent person—it is so preposterous that I would give someone else that power over me, and it often snaps me out of a bad mindset and reminds me to be the controller of my own mind.

These principles at the top are in many ways quite reactive, ways of dealing with difficulty. They are usually enough to quell anger for me. They are also all related to what is sometimes called Stoic mindfulness, so I sometimes imagine that as another over-arching title for the whole section. (Note: it’s probably a good idea to start with a simple scheme and once you have that on autopilot, you can add some additional elements / secondary associations.) The simple word ‘mindful’ is often a powerful reminder to me to notice if my mind is running away with itself and to reign it back in.

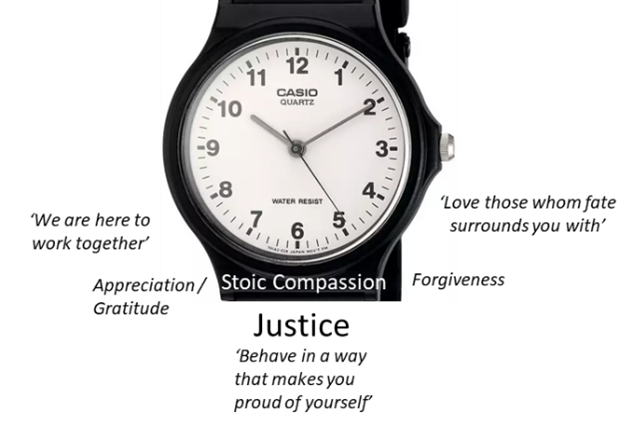

So, while these principles deal largely with dealing with difficulty, in the lower realm, near justice (or social virtue), I put principles that are closer to the concept of compassion, and which I find valuable as a proactive practise (but also as a secondary reactive). At ‘8’ I have ‘We are here to work together’ and at ‘4’ I have ‘Love those whom fate surrounds you with’. These are both paraphrasings of Aurelian passages. I really like the latter, it uses ‘love’ as a verb, putting it ‘in your power’, an important reframing of our common use of it as something we either feel or we don’t. It creates a powerful mental flip for me, very often instantly leading to a kinder orientation and better behaviour.

Below these at ‘7’ and ‘5’ I have two phrases that are more from common language than Stoicism per se (although the ideas are there too) but make sense here and I find very useful. They are ‘Appreciation / Gratitude’ and ‘Forgiveness’. These don’t need much explanation but also remind me to value the good things about the people around me and to let go of their failings. Forgiveness is often my final tool for letting go of any lingering anger when other principles have failed. Ok, yes they did that to you, you aren’t imagining it, and it was wrong, now let’s just let it go.

While the top half of the watch face can therefore be captured quite well with the phrase ‘Stoic mindfulness,’ this lower half can be captured quite well with the phrase ‘Stoic compassion’ (big thanks to Donald Robertson for his articles introducing me to these terms). Because the Stoic concept of ‘justice’ doesn’t translate well into English, I also label this ‘social virtue’ in my mind. I use this point to remind myself that I need other people, I am a social being, and I will get back from people what I put in. To this end I also often use the phrase ‘Behave in a way that makes you proud of yourself’ as a subheading to ‘Justice.’ This might be my most powerful phrase, reframing situations from a focus on others’ behaviour to my own as well as towards my own judgement of my actions, rather than relying on others’ opinions. It also often reminds me that the most difficult situations that some might consider disasters are in fact opportunities to make myself proud.

Going through the whole watch face, all the principles combined, make for a very nice 5–10-minute proactive meditation when you have a chance. Reminding yourself of how you want to deal with difficulty,2 and how you proactively want to treat other people. Sometimes, I visualise myself standing on the watch face at 12 (Wisdom), looking at 6 (Justice) with the discipline of desire and aversion in one hand to my right, and the discipline of assent in the left hand, as my most powerful mental tools, and the others available if I need them. With this perspective I am pointed toward justice (or social virtue, or the discipline of action) as my ‘path’ forward, which is the ultimate aim, and these three are really just tools to achieve that aim. This directionality is nice, I think, as it is a common Stoic trap to get stuck in the top quadrant of this watch face, with the disciplines of desire and aversion and assent, and never get round to proactive social service.

Now getting into a bit of habit theory. Once you have a strong habit of, during a period of difficulty, mentally going to this space (p.s.—unless a clear relevant bit of specific wisdom naturally comes to mind, starting at the top with the general ‘wisdom’ / ‘handle this with wisdom’ is a good default), you might not really need the physical watch anymore. However, getting to that point is not trivial. There are a few things you can do to make sure your watch effectively acts as a reminder and doesn’t just fade into the background (its prominence on your wrist is both a blessing and a curse in this way). One value of a watch for this is that most of us take it off at night and put it back on in the morning. These morning routines are generally very good times to attach rituals such as short meditations to (known as ‘habit stacking’—brushing your teeth is another good time, two minutes twice a day where you can’t really do anything else). Try to get into the habit of reminding yourself, when you put the watch on each day, of its role as a reminder of this framework. While you dress yourself you are physically preparing for your day, so make this a moment to mentally prepare for it too. If you have the time during this period to rehearse all the ideas associated with each point on the watch this will help too. This could be anywhere from a 30 second literal rehearsal of the words to a 5- to 10-minute sit down meditation where you imagine the most likely difficulties of the day and prepare to use these principles to handle them in a way that ultimately makes you proud of yourself.

Good luck out there!

About the Author

Stephen Dewitt is an associate professor in cognitive psychology at University College London. He studies human reasoning with a focus on confirmation bias, belief polarization, uncertainty and ambiguity. As well as the ethical and practical value of Stoicism, he is interested in techniques such as the discipline of assent for improving human reasoning. His Stoic practise informs his academic critiques of modern narrow uses of rationality and logic that are often seen in tech circles. He is currently working on a book titled The Rationality Myth which provides a critique of these ‘hard’ (usually mathematical) ideas around what counts as good thinking.

In truth the mental visualisation has become such a powerful habit for me I don’t really need the watch itself as a reminder anymore, although it was useful in the early days (and I like having a watch anyway…).

One important principle missing from my watch face is negative visualisation. However, this is where that comes in. My Stoic meditations begin with this, and the principles on the watch face are the tools I imagine using in response to that anticipated difficulty.

An Ah! Ha! moment. This idea really resonates with me. I'll be setting up my own dial over the weekend. Thank you.

This is so incredibly practical. Thank you.